By Alicia Perkovich, Gallery Assistant Intern & Heat Exhibition Specialist

In the last two Heat blog posts, we’ve introduced common ways to visualize heat— most recently its idyllic depiction in summer landscapes. But for today’s artists, heat may not be associated with leisure, but with dread. This post will show how Touchtone artists Patricia Williams and Gale Wallar visualize the heat of climate change. Additionally, we’ll show how these artists’ different styles exist alongside the broader movement of climate change art.

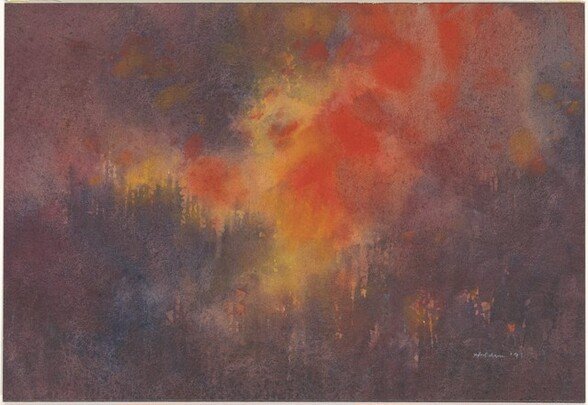

Patricia Williams Wildfire I

On display this month in the HEAT member show, Patricia Williams’ Wildfire I, Wildfire II, and Wildfire III are a watercolor triad inspired by the California wildfires. Wildfire I and Wildfire II appear as either abstractions zoomed in compositions of a raging fire, with billows of orange and yellow colors moving throughout the image, enveloping any resemblance of a typical natural landscape. In Wildfire III we see brown trees along a hill in the foreground, with an orange mass of fire creeping behind it, having already burnt nature in its path. The watercolor medium allows for the burgeoning shapes to appear just as volatile as wildfire, creating a range of colors that can visualize the chaos of both a raging fire and burning natural landscape.

Patricia Williams Wildfire II

Speaking of her Wildfire series, Williams says she “was struck by the contrast of the beauty of the images with what I knew to be the terrible destruction and loss of life taking place. Are beauty and destruction always companions?” To Williams, climate disasters such as wildfires may be visually stunning, but in the end that beauty reminds her of tragedy— the tragedy of destruction, as well as the shame that humans should feel for their responsibility for that destruction.

Patricia Williams Wildfire III

Williams’ small-scale landscapes, focused on the shapes and volatility that show the essence of a wildfire, draw inspiration from the American watercolor artist Donald Holden, whose works such as Yellowstone Fire XIX take on a similar subject matter, although Holden’s technique of starting with dark colors and gradually moving onto lights contrasts the brightness of Williams’ triptych.

Donald Holden Yellowstone Fire XIX

The sublimity of these watercolors— meaning the awe-inspiring beauty of something larger than human life, which can inspire great feelings of spirituality and transcendence, but also terror and fear— harkens back centuries to Romanticism artists, who, witnessing an expansion of human power over the environment, were inspired not by human achievement, but by natural resilience.

Caspar David Friedrich The Sea of Ice

Romanticism was a European artistic movement that gained popularity in the early 19th century. At this time, the Enlightenment and its values of reason, order, and human power— as travel and imperialism were proliferating— were popular, and Romanticism proposed an alternative framework. Focusing on the movement’s views on nature, Romantic artists stressed the unpredictable and unyielding power of nature, despite the human hubris to conquer it. The Sea of Ice, by leading Romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich, visualizes this with the sharp, giant sheets of ice that swallow a shipwreck, showing the victory of nature over humans, as well as the hostility of nature. Yet despite all of this, the ice remains beautiful in its clear lines and dramatic shape— creating the sublime beauty that Romanticism treated nature with.

While Williams’ Wildfires evoke the same power of nature, we might see this power as a swan song of nature’s powers, since recent wildfires have been the result of human activity. While these disasters may, for a moment, be sublime, they are bookmarked by human-generated climate change, which in the end may leave nature powerless.

Gale Wallar Aletsch Glacier, Switzerland

Gale Wallar’s acrylic painting Aletsch Glacier, Switzerland also reflects the negative impact of climate change’s heat, but in cold regions. The Aletsch Glacier is part of the Alps, located in Southern Switzerland. Fourteen miles long, this glacier has been melting at an alarming pace, adding to rising sea levels and threatening the livelihood of mountain communities and their economies.

The bright, cloudless sky in Aletsch Glacier, Switzerland, along with the brown, iceless peaks and hollow valleys, are the details by which Wallar visualizes the melting glacier. With poignant realism, the painting seems photographic, and Wallar takes on a dual job of painter and photojournalism.

Edward Burtynsky Anthropocene

This method of artists documenting climate change similar to journalists is common, and best seen in German photographer Andreas Gursky and Canadian photographer Edward Burtynsky. Gursky is known for his landscape photographs which capture large-scale settings. For example, his photograph Antarctic (2010) is a collection of satellite images which capture the entire continent. With its high quality, we can see the ice melting off in real time. Burtynsky, through his ongoing series Anthropocene, works at a similar scale and aesthetic, although his subject matter is how human industry harms the environment— in the end depicting “the landscape of human systems imposed in nature to harvest the things that we need." Philosopher Timothy Morton has described climate change as a “hyperobject,” something so big that, while we can see examples of it, we can’t observe or even understand its totality. This second method of documenting climate change, contrasting from the sublime, emotional work of Williams, as an attempt to approach the hyperobject of climate change.

Andreas Gursky Antarctic (2010)

Lastly, in the genre of climate change art, site-specific exhibits and installations are popular as they literally ground art in vulnerable environments For example, the 2018 exhibition Indicators: Artists on Climate Change, in the Storm King Art Center in Hudson Valley, New York, hosted the climate-change art of 17 contemporary artists who created climate-related sculptures, installations, multimedia works, and earth-works. For example, Mary Mattingly planted tropical fruit trees from Florida in the art park to speak on how global rising temperatures may force a repurposing of environments to maintain current markets and lifestyles— such as harvesting coconuts in Upstate New York— and David Brooks made bronze castings that replicate natural objects in Storm King’s forest, acting as time capsules as climate change will continue to alter the landscape.

Mary Mattingly Along the Lines of Displacement: A Tropical Food Forest, 2018

Through two of our member artists and a brief survey of the climate change art movement, we’ve outlined three distinct ways that artists depict climate change, and how heat relates to all of their work. We hope that this blog post can be informative in how you look at your own changing landscape, and the role of contemporary art in documenting it. To view Patricia Williams’ Wildfire works and Gale Waller’s Aletsch Glacier, Switzerland, along with the other works by our artists, visit the HEAT member show, open Wednesday-Sunday from 12:00PM-5:00 pm until July 31.